Retracing A 100-Year Leica Mystery

Searching for the echoes of Wetzlar in West Greenland

Earlier this year, I learned that I’d be travelling to West Greenland for a special project. On the surface, I was thrilled to check off another bucket-list destination, but beneath that excitement was a deeper pull. This chance to explore the region’s culture and history. For many, Greenland exists only as a vast white void on a world map, a place of ice and silence. I wanted to confront that idea. What I didn’t expect was to find myself chasing the ghosts of a century-old expedition.

In the months before my voyage, I stumbled upon a story. One rooted in exploration and tied to the early legacy of Leica, the brand behind my cameras of choice. It was the kind of connection that stops you in your tracks, a thread linking past and present in the most unexpected way. I followed it, and what I uncovered would give my journey to Greenland a new sense of purpose. One that would turn this trip into something far more profound.

Note To Readers

This is a longer story and if you’re reading this in email, there’s a good chance it may not load properly. This story is best experienced on Church & Street or through the Substack app.

For Science

In the summer of 1925, the First Hessian Greenland Expedition set sail for the west coast of Greenland. Led by geologist Hans K. E. Krüger and guided by geography professor Fritz Klute, the mission was simple in purpose but ambitious in scope. They sought to gain experience in the Arctic and collect geological data for a much larger second expedition.

What made this journey remarkable was not only its scientific intent but the tool Klute carried with him. In his hands was a prototype Leica 0-Series, one of the first 35mm film cameras ever built.

Created by Oskar Barnack, this camera redefined what photography could be. It was compact, portable, and built to survive the elements. For the first time, a compact camera could travel with explorers into the harshest corners of the world.

The team used it to document their work, capturing more than 700 photographs of West Greenland. According to Krüger, over eighty percent of their exposures were usable despite the unforgiving conditions. The results were a triumph for both the scientific community and Leica itself.

Then, the images disappeared.

It is believed that every photograph and negative was destroyed during an air raid on the town of Giessen on December 6, 1944. What remained was a gap in history, a story trapped in the ice, waiting to be rediscovered.

Rebuilding the Story

A hundred years after the First Hessian Expedition, I found myself tracing their footsteps with a Leica of my own. Picture it. The year is 2025, the centennial of the first production Leica camera. I’d been given the privilege of serving as a global ambassador for the fastest Leica ever built. Then came another call. This time, to create a story that paired that camera with new lenses from Leitz Cine, lenses inspired by the optics that helped shape Leica’s legacy. The setting would be the same stretch of West Greenland that Krüger and Klute explored a century earlier.

This is where the creative journey begins to feel unreal. As if history itself had quietly set the stage.

Armed with Leica’s modern SL bodies, engineered to endure the world’s harshest environments, and Leitz Cine’s new HEKTOR lenses, reborn from the glass of the past, I had the perfect tools to chase my own story. Yet what drove me most was not these tools but the purpose behind it. With every photograph I’d carry this connection to century old legacy. And each day would reveal a new layer of that legacy.

Sermilinguaq Fjord

After embarking our ship in Kangerlussuaq, we set sail for Sermilinguaq Fjord. For the uninitiated, a fjord system is a long, narrow, deep inlet of the sea that cuts between these steep cliffs, typically carved by ancient glaciers. In simple terms, it’s where prehistoric stone and ice meet the ocean. And this one made quite the first impression.

It’s hard to describe the feeling of standing before these giant, monolithic walls of nature. They rise high above the water, their surfaces carved by time, while below them, turquoise seas swirl with glacial runoff. The water had this vibrance to it, as if someone took a Tiffany box and punched up the saturation.

The collision of texture, colour, and scale feels almost alien. You can only imagine what the early explorers must have thought when they saw this for the first time, especially without the benefit of colour film to capture it. Seeing it in person is nothing short of breathtaking. It was the perfect introduction to West Greenland.

After a healthy amount of exploring on Zodiac, we made it to land for a quick hike. My eyes were immediately drawn to the ground, where pockets of mustard, mandarin, and maroon were peppered across the beach. I’d travelled to Svalbard and the Antarctic previously, so seeing these colours so close to the Arctic circle felt unique. It was a moment that’d inform a lot of what this trip would have in store.

Amerloq Fjord & Sisimiut

The following day, after a morning cruise along Amerloq Fjord, we arrived in the town of Sisimiut. With a population of just over 5,500 people, it stands as the second-largest town in Greenland. It was also home to two of the incredible chefs aboard our ship. Sisimiut sits just above the Arctic Circle and has been inhabited for at least 4,500 years. The weight of that history is hard to describe.

What made this visit special was that it gave me my first real chance to connect with the people of Greenland. People who have called this place home for generations. I spoke with locals about their upbringing, their traditions, and the rhythms of their daily lives. Every conversation revealed a quiet resilience, shaped by the elements and the land itself. One theme echoed again and again: the bond between the people and their Greenlandic sled dogs.

These dogs carry a presence that’s almost ancient. You can sense the wolf within them, a spirit that refuses to fade. Every sled dog in Greenland is a working dog, born and raised outdoors. They live in what locals call “dog towns,” small clusters just beyond the edge of human settlement.

We were fortunate to visit one of these places and spend time with the dogs, and even a few of the pups. Standing there, surrounded by the sound of howls carried through the Arctic wind, I was reminded of how long this partnership has endured. For thousands of years, humans and dogs have crossed the ice together, each surviving because of the other. Simply remarkable.

Qeqertarsuaq & Kuannit

On our third day, we made our way to Qeqertarsuaq, a town first settled by whalers in 1773. Archaeological evidence suggests that people lived here as long as six thousand years ago. What makes this region truly unique is that it sits on the only volcanic ground in all of Greenland.

Qeqertarsuaq felt different from every other place we had visited, and even from those still ahead. The geology here feels almost foreign to the rest of the island, full of colour and texture. In summer, the landscape comes alive with a lushness that feels unexpected this far north. The volcanic soil creates a special ecosystem where, as far as I know, more than half of Greenland’s plant species can be found. And tucked within this wild setting is one of Greenland’s few outdoor soccer fields, framed beautifully amongst the icebergs in the distance. It’s an image that lingers in your mind long after you leave.

Later that afternoon, we climbed back into our Zodiac for a cruise along Kuannit, and it was here that I was reminded of what drives my polar work. It’s what keeps me returning to these frigid frontiers.

If you look closely at this photograph, you can see a small bird near the top left of the frame. That little speck of life reveals the staggering scale of the ice around it. Even though these aren’t the largest icebergs in the world, they have a way of humbling you when you get close. The size, the structure, and the shades of blue come together like a living sculpture. It feels both alien and sacred, and it reaches deep into something primal within you.

Bjørnefælden & Napassuligssuat Valley

Our next landing point was Bjørnefælden, which translates to “The Bear Trap.” It sits just north of Disko Island, a place that still holds a quiet mystery. Scattered across the landscape are old Norse structures whose purpose remains uncertain. Some once believed they were used to trap polar bears, while recent research suggests they may have served as graves or cenotaphs.

From there, we set out on a hike through Napassuligssuat Valley. The fog rolled in thick and low, wrapping the terrain in silence. The setting felt otherworldly, and while I wasn’t necessarily seeing something profound through my lens, I was feeling something powerful. There was an unease in the air, a quiet sense that the land was watching.

I found myself surrounded by fellow travellers and expert guides, moving through this vast space with a sense of safety that early explorers never had. For them, every sound, every shadow could have meant danger. The same fog that I used to shape my composition might’ve concealed something far more threatening for those who came before us. That thought stayed with me throughout the hike. It reminded me how much respect is owed to those who ventured into the unknown, chasing stories to the ends of the earth in the name of science.

Uummannaaq

Next on our journey was the town of Uummannaq, a small island community of about 1,300 people. What makes this place special is the mountain that rises directly behind it, a dramatic peak that dominates the skyline. I’m sure landscape photographers dream of scenes like this, but what truly caught my attention were the faces of the people who call this place home.

Visiting Uummannaq gave me another chance to connect with the locals and hear their stories. Every conversation felt like a spark that recharged my creative energy. What moved me even more were the stories carried through generations in the form of song and music. There was a rhythm to the way history lived in their voices, and that experience became the emotional anchor for the piece I’d later created around the Leitz lenses I was using.

We ended the day with a Tundra to Table dining experience on the ship led by the two chefs I mentioned earlier, Mikki and Iben. A small group of us gathered to enjoy a tasting menu built entirely from the ecology of Greenland. To say it was delicious wouldn’t do it justice. It was transcendent. Every bite revealed a new flavour or texture that seemed to echo the landscape itself. Experiencing Greenland through taste gave the scenery around me a new dimension. My only regret is knowing it may be a very long time before I get to taste that menu again.

Eqip Sermia

After one of the best meals I have ever had and a full night of rest, our group arrived at Equip Sermia. This site is home to one of the most active glaciers in all of Greenland. It’d also be the setting for an experience unlike any other: a helicopter flight over ancient ice.

Thousands of years of cold and compression have shaped this landscape into something extraordinary. From above, the glacier looked like the surface of a meringue pie. Scattered across the ice were brilliant pools of sapphire blue that shimmered in the light. The view was beyond anything I’d ever seen before.

It also struck me that the explorers a century ago might never have witnessed this sight. The terrain is harsh and unforgiving, a place that would’ve challenged even the most seasoned among them. To soar above it, to see the scale and structure of this frozen world from the air, was a privilege that was not lost on me.

Sea Day

From the moment we stepped aboard the Ultramarine, we experienced Greenland at a breakneck pace. Two excursions a day, multiple lectures, and a steady stream of conversations with new friends made every hour of this trip full and vivid. It was a journey rich in discovery, but also one that demanded every ounce of energy.

By the second last day, when the announcement came that we would have a full day at sea before reaching our final destination, a collective sigh of relief moved through the ship. Everyone was ready for a moment of intentional rest.

This day gave me the space to slow down and reflect on everything we’d seen so far. I spent the better part of the morning just watching the water, letting the stories and emotions flow through me. It’s difficult to explain, but near the end of every expedition, there always comes a day like this. A quiet pause before the return to normal life.

I’ve learned to value these moments. They allow the noise to fade and the meaning to surface. It’s often in this stillness that the seeds of my future stories begin to form.

Eternity Fjord

Our final day brought us to Eternity Fjord, a name that could not have been more fitting. Stretching nearly 75 km, this region was carved by ancient glacial ice where streams of meltwater spill into the sea.

The sun broke through the clouds like a torch splitting the sky. It created a sight so powerful that, if I’m being honest, no photograph could ever do it justice. As we drifted through that vast silence, my thoughts returned to the early explorers. I imagined Krüger and Klute moving through these same waters, surrounded by mountains that towered far beyond anything they would’ve seen in their homes in Germany.

To translate what they must have felt into words or images feels nearly impossible. Yet they tried. With a modest little camera that would one day change the world of photography, Krüger and Klute sought to capture the feeling of discovery and share it in the name of science. Standing there with a Leica of my own, I felt the weight of that same calling. What a privilege it must’ve been to see this world for the first time. And what a privilege it still is today.

A Trip For The Ages

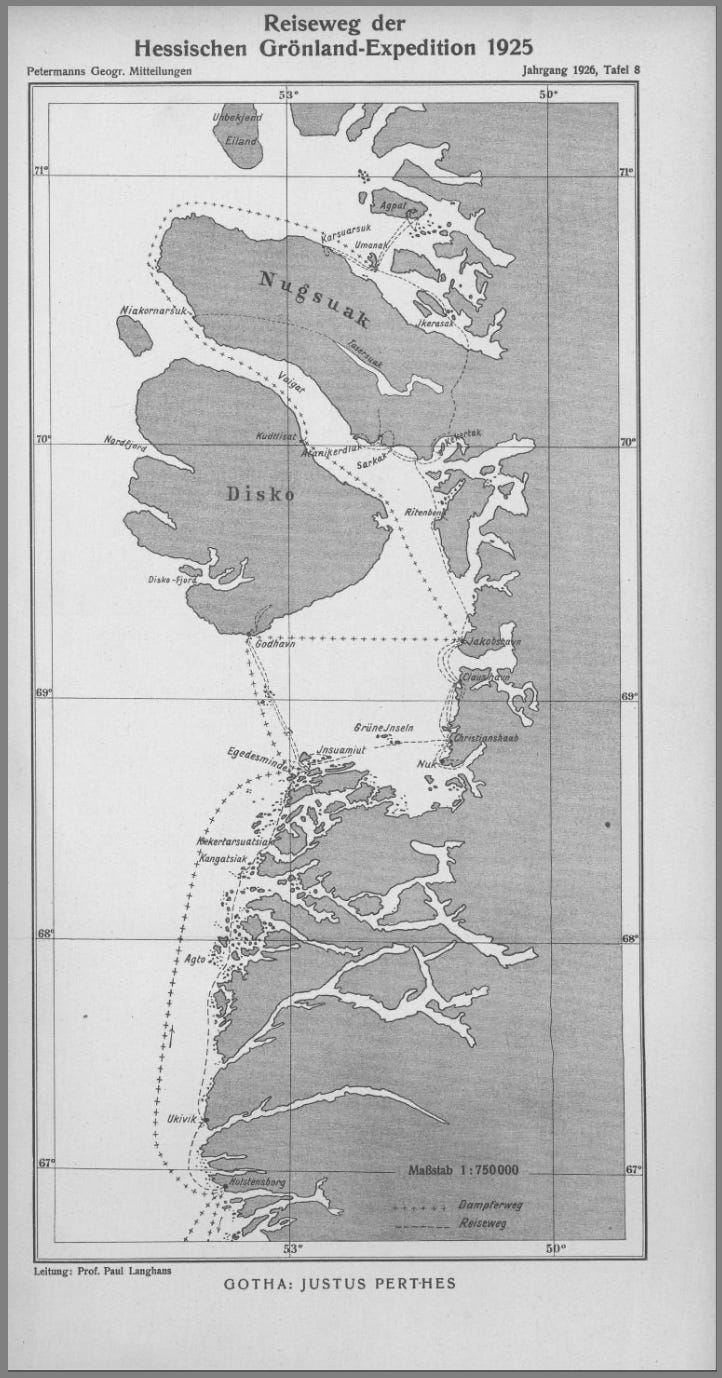

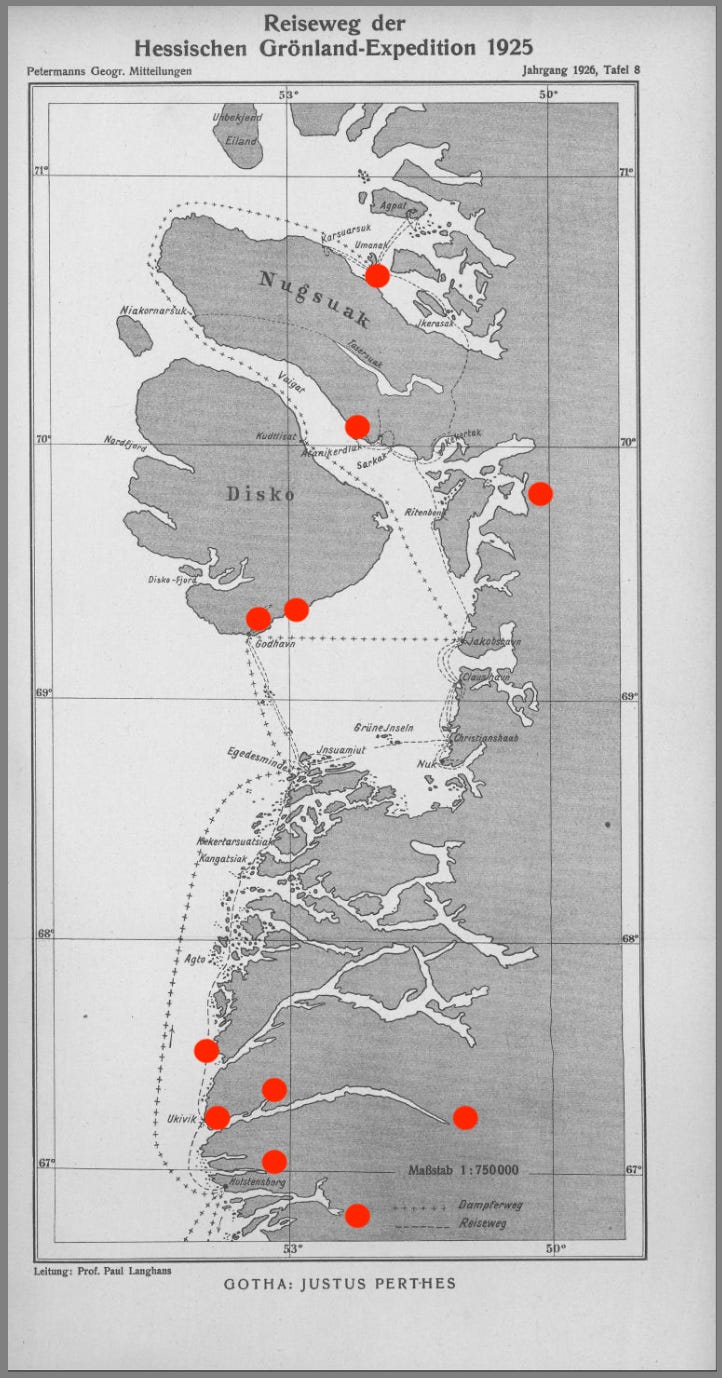

After returning from the trip, I barely had time to take it all in. I was quickly thrown back into preparing assets, talks, and workshops, slipping into a rhythm that felt all too familiar. Weeks passed before I finally had a quiet moment to reflect. That’s when I began piecing together this story, starting by plotting the points I had visited on the same map used by the First Hessian Greenland Expedition.

My jaw dropped. In the chaos of travel and work, I had never noticed how closely my voyage mirrored theirs. A hundred years apart, yet the paths seemed to run side by side. I’d been so focused on the present that only with distance could I see the symmetry. It made the entire experience feel profoundly connected, almost as if time itself had folded in on this one journey. This is what makes the creative process so powerful.

It’s in moments like these that photography feels less like documentation and more like communion. The mystery I’d been chasing was never about finding what Krüger and Klute left behind or recreating their images. It was about channeling the curiosity that drove them forward.

Standing on that bridge between past and present, I realized the truth behind it all. Some stories don’t have closure. Sometimes they’re meant to be lived, again and again.

Upcoming Events & Workshops

Mexico City: Día de Muertos Meet-Up

I’ll be in Mexico City in early November for Día de Muertos and planning a few free meet-ups and talks. The main event is on Monday, November 3rd and you can register for free here.

Toronto Studio Photography Workshop

This November, I’m hosting a studio photography workshop designed to elevate your skills. Whether you’re a beginner looking to build a solid foundation or an experienced photographer looking to refine your craft, this workshop will educate you in the essential techniques of studio work. Full details can be found here.

Arctic 2026 Photography Adventure

In 2024, I traveled to Svalbard with Quark Expeditions and it was unforgettable. I’m planning a return trip in 2026 with a group of photographers. This is not a workshop. It’s an excuse for like-minded storytellers to visit one of the most remote places on earth. If that sounds like you, fill out this form to learn more.

Next year, I’m heading to India again for our second street photography adventure across the North and South. Seats have just been made available for those looking for a deep, immersive photography experience. Learn more here.

Previous Favourites

October Contest

This month, I’ll be giving away a $200 gift card to the Moment Shop where the winner can save big on their next camera, lens, bag, or courses. Moment has so many creative products to choose from and $200 can absolutely make for a great deal.

How will I pick the winner? Make sure you’re signed up for this newsletter then leave a comment on at least one post from this month. I’ll be randomly picking one person, confirming they meet the requirements and contacting them directly before announcing the winner publicly.

As always, this contest is void where prohibited by law. Good luck!

My thanks to the team at Moment! Not only for this contest but for being the longest supporter of my work online. They’re a lean team of passionate creators that truly believe in supporting other creatives on their journey. Whether it’s a new camera, lens, workshop, or just some great articles, visit ShopMoment.com today.

What’s Next?

Before I wrap this up, I want to thank the team at Quark Expeditions. I’ve been partnering with them for years, and getting the chance to travel to this part of the world to continue my polar work has been nothing short of incredible. My gratitude also goes out to the community of West Greenland, who welcomed us with warmth and shared their stories so openly. It’s something I’ll carry with me for a long time.

This story took time to put together, but it deserved that time. If you enjoyed it, I’d be grateful if you shared it with someone who might appreciate it too.

With this now in the archive, I’ll be returning to my regular weekly schedule—maybe even a bit more often—as I start sharing new pieces from the adventures that followed my journey through Greenland.

See ya next time!

GB

What can I say, this latest Greenland newsletter is one of the best written travelogs I have ever read in or out of the photography space. The pictures are fantastic to boot. Nice job man!!!

Storytelling! Brings images to life. Excellent.